Alumnus's journey includes role identifying new marine reptile

May 1, 2020

Elizabeth Talbot

907-474-2619

Eric MetzŌĆÖs timing could not have been better when he chose to seek a masterŌĆÖs degree in paleontology at UAF. Metz was interested in ancient marine reptiles, which led him to a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to study with Patrick Druckenmiller at the ┬ķČ╣╣┘═° Museum of the North.

In 2014, Metz was working on his undergraduate degree at Montana State University, the same place Druckenmiller earned his masterŌĆÖs degree.

ŌĆ£I had made it known to the paleo faculty and some of the grad students that I liked marine reptiles,ŌĆØ Metz said. ŌĆ£And they were like, 'You should email this Pat guy.'ŌĆØ

Druckenmiller helped Metz with his undergraduate thesis. ŌĆ£And after that I still wanted to study marine reptiles, so I moved on up (to Alaska).ŌĆØ

Luckily for Metz, the move happened three years after Druckenmiller had been part of a startling discovery on a beach in Southeast Alaska. The fossilized remains of a new thalattosaur species, a type of marine reptile, were embedded in a rock. The rock was shipped to the collections at the museum, where Druckenmiller is the curator of earth science.

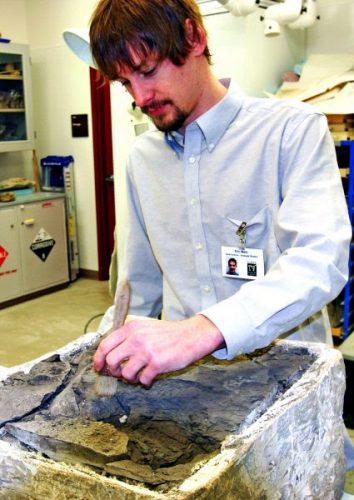

Metz joined the team working on the specimen in fall 2014 as a new graduate student at UAF.

ŌĆśCut that thing out now!ŌĆÖ

The fossil discovery happened in May 2011 during a minus tide, which occurs only twice a year near the summer solstice. Gene Primaky and Jim Baichtal, U.S. Forest Service co-workers in the Tongass National Forest, were exploring a beach normally submerged in ocean water. The extreme tide revealed gorgeous pink shells and brachiopods galore.

Primaky and Baichtal were moseying around the Keku Islands near the village of Kake when they discovered the amazing 3-foot fossil.

ŌĆ£I thought it was a fish at first,ŌĆØ Primaky said. But as he took a closer look, he called out to Baichtal, who instantly recognized it as a fossil. They immediately sent several photos to Druckenmiller.

ŌĆ£Pat said, ŌĆśThat is a lizard, not a fish,ŌĆÖŌĆØ Primaky said. And then he said, ŌĆ£Cut that thing out now!ŌĆØ

Appreciation for paleontology

Metz was instantly drawn to the fossil project waiting for him at UAF, something his advisor was counting on. ŌĆ£I actually sent Eric to Europe to go look at some material,ŌĆØ Druckenmiller said. ŌĆ£We pulled all this information for our comparisons and it was really clear this was a very different animal. But we needed to detail those differences. All that comparative work was important.ŌĆØ

Metz spent about two weeks in Europe looking at holotypes of other thalattosaurs at different museums. Although Metz was a geology student, he always had a passion for paleontology and the field work it requires.

ŌĆ£Paleontology is attractive to me because it requires a knowledge of multiple fields to be successful,ŌĆØ he said. ŌĆ£You need to know very detailed aspects of both geology and biology to understand paleontology. I really enjoy walking around a landscape looking for fossils that no one has ever seen before. It is a very surreal experience.ŌĆØ

The more we learn about EarthŌĆÖs inhabitants before our time on the planet, the more we are able to understand our present and our future. The fact that thalattosaurs were bookended by two mass extinctions may help us understand our planetŌĆÖs natural fluctuations.

The comparisons Metz made during his excursion to Europe played a vital role in the teamŌĆÖs ability to be certain that their fossil was unique and the first one of its kind.

Such a unique creature requires a name that sets it apart from the rest. The team was advised by Ray Troll, an artist whose work depicts scientific creatures with a humorous flair, to use a Tlingit name to honor the creatureŌĆÖs discovery site. Gunakadeit is a sea monster of Tlingit oral traditions that brings good fortune to those who see it. The second part of the name, joseeae, was chosen by Primaky, who found the fossil. He named it after his mother, Jose├®.

Geological time

The amazing find changed the trajectory of the rest of MetzŌĆÖs academic career. It led to the inclusion of Gunakadeit joseeae in his thesis. He is currently awaiting publication on a study about a similar thalattosaur recovered from Central Oregan.

The opportunity to mentor other students in the paleontology program inspired Metz to choose a career path that would allow him to educate others and share his passion for science. Although he dreams of returning to Alaska someday, he is currently the lab manager of the Varricchio Paleontology Lab at Montana State University.

ŌĆ£A friend told me once that Alaska gives you what you put into it,ŌĆØ he said. ŌĆ£I really believed that. There was always something interesting to do outside no matter the temperature, and the people there were always ready for an adventure. I appreciated that. I always felt like I could get lost if I wanted to.ŌĆØ

MetzŌĆÖs appreciation for his time at UAF and for his mentor Druckenmiller is apparent. ŌĆ£I liked the feeling that my studies were important," he said.

"UAF was fun," he added. "It was different from my undergrad but in positive ways. I liked the hill that separates campus and the upper and lower sections. The view from the museum was the best in town, in my opinion.ŌĆØ

And he has the discovery of a new species of thalattosaur to build his career on. Across millions of years, Gunakadeit joseeae traveled thousands of miles along the coast of North America, buried beneath water and sand, waiting, preserved for the convergence of the perfect summer solstice tide and the right humans to discover it.

Sometimes, timing is everything.